The beauty of folk beer styles is the degree of variation they can take from one brewer to the next. Recipes are dictated by what grows locally and what is in season, making for a beer that reflects the true local flavor.

Kvass, an ancient Russian beer, is one of those styles that can take many forms depending on where and at what time of year it is brewed, but at its core it’s always a low alcohol (<2% ABV) bread-y beer with a slight sour tartness.

A Drink for the Masses

Kvass, like many of the oldest-known beer styles, was likely discovered by accident. Some lucky person drank the water-bread mixture that had been sitting out for a few days and decided what it had turned into was something worth making again.

In its earliest form, loaves of old bread and/or flour were simply soaked in hot water. Wild yeast was relied upon to spontaneously ferment the concoction, which gave it the signature reserved tartness. In some instances, some of the small batch breweries would add whatever ingredients were available locally, but it wasn’t uncommon to go without.

After a few days, the bread-y mixture ferments up to 2% ABV and the entire contents—solids and all—would be consumed. This made for a great source of nutrition, while also turning undrinkable water into something potable.

As the allure of kvass shifted from a thing of utility to a lively beverage to be imbibed, the process was refined. Wild fermentation was ditched for something cultured. The commercial kvass breweries would sometimes use brewer’s yeast, but the small batch and home breweries would typically use a baker’s yeast culture. Then, local ingredients were added to add interesting flavors.

Fruits like strawberries and dried grapes added more intriguing sweetness to the flavor, while also balancing some of the Lactobacillus sourness. Lemon is a more recent addition that has become popular to add a citrus compliment to the Lacto, and even herbs and spices like peppermint have been used.

Eventually, kvass reached a point of popularity in Russia and its neighboring countries that spanned from common peasant to royalty. Street vendors pushed carts equipped with a large cask-like tanks to peddle kvass to passerbys. Some even say kvass is one of Russia’s most treasured culinary tradition, second only to sauerkraut.

Today, commercial breweries continue to brew kvass in Russia and homebrewers carry on with the tradition of putting their own twist on an ancient style by using unusual ingredients and pushing the strength up towards 5% ABV. The popularity of kvass even led to a non-alcoholic version that essentially captures some of the flavor qualities in a soda-like beverage.

Making Kvass

One of the oldest known kvass recipe is quite simple, and is still easily made today with varying results. A loaf of rye bread, typically something about to go bad, is placed in a vat and boiling-hot water poured over it. The bread soaks in the water for 24 hours, after which sugar and a yeast starter of baker’s yeast and flour are added. As soon as fermentation begins, it is bottled to add a bit of carbonation and is consumed fresh 2-3 days after.

A lot of kvass brewers would forgo the bread and use flour as the base, but a rye loaf can add lots of interesting crusty bread and other sour qualities that flour might not achieve.

One of the other key components of kvass flavor is the Lactobacillus sourness. It is not lip puckering, but adds a refreshing hint of tartness that really compliments the flavors of a rye bread. While you can still rely on a 100% wild fermentation, some brewers will try to cultivate their own wild yeast or use a combination of ale yeast and a Lactobacillusculture. Others have simply forgone the bugs, sticking with ale yeast and relying on ingredients like lemon juice to achieve a sour component.

From there, you can add other ingredients you think might compliment the profile. In addition to what was mentioned above, grains, hops, different yeast styles, herbs, spices, fruits vegetables and just about everything else could make its way into the recipe. If you want to hold true to kvass traditions, utilize ingredients that are grown locally and are in season at the time of brewing.

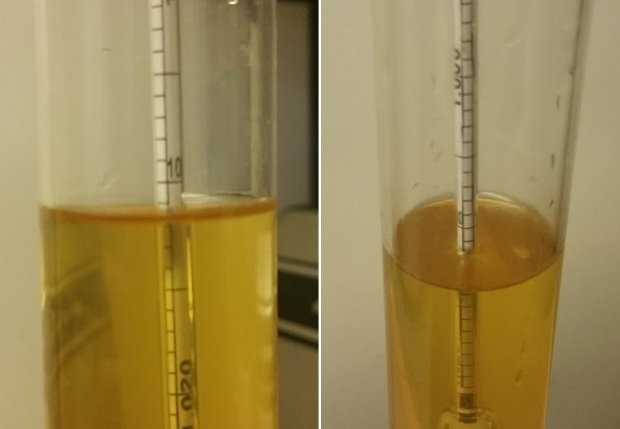

Being a low gravity beer, kvass finishes fermentation fairly quickly and has always been intended to be enjoyed fresh. There’s no need to let this one sit. Carbonation levels vary and traditionally was achieved through bottle conditioning.

Check out this

kvass recipe, which uses modern techniques to create a brew that honors the Russian drink. It even includes a recipe for making your own rye bread!

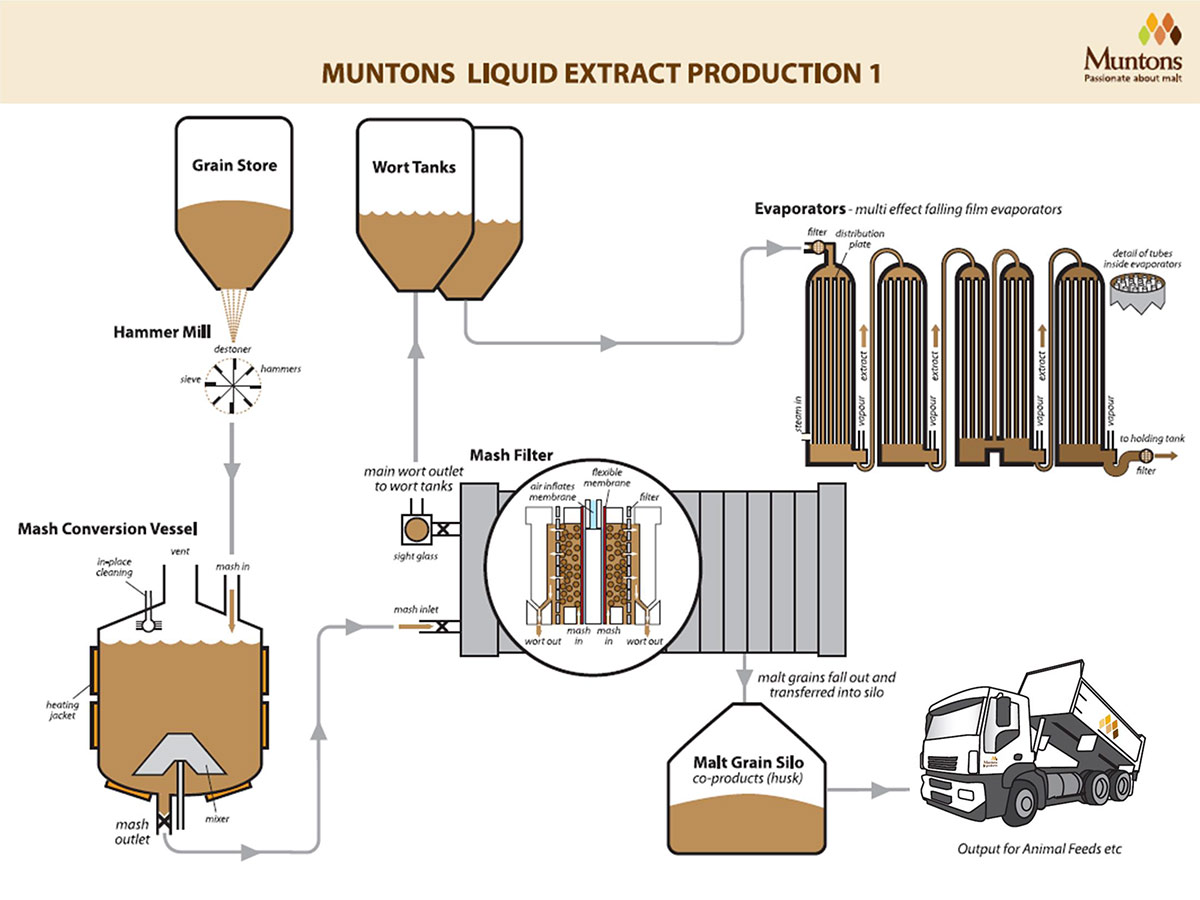

Once the mash is complete, the sugary-sweet wort is sent through a pipe to a filter. The filter helps separate out the spent grain sediment, while sending the sediment-free wort to holding tanks. If a malt extract is hopped, it will often times undergo a boil in one of these tanks to promote isomerization.

Once the mash is complete, the sugary-sweet wort is sent through a pipe to a filter. The filter helps separate out the spent grain sediment, while sending the sediment-free wort to holding tanks. If a malt extract is hopped, it will often times undergo a boil in one of these tanks to promote isomerization.

The process of building a draft barrel was a bit more difficult than converting a cooler, however the hardware and tools required were essentially the same.

The process of building a draft barrel was a bit more difficult than converting a cooler, however the hardware and tools required were essentially the same. The next step was to decide if it would use a plate chiller or stainless tubing for heat exchange. Given the shape of the barrel and the availability of plate chillers, I chose to use tubing. Using some rough math, the thermal conductivity of 304SS and the space limitations of the barrel, I concluded that 35 ft. per coil would be sufficient to produce a serving temperature of 45 degrees or less depending on keg temperatures.

The next step was to decide if it would use a plate chiller or stainless tubing for heat exchange. Given the shape of the barrel and the availability of plate chillers, I chose to use tubing. Using some rough math, the thermal conductivity of 304SS and the space limitations of the barrel, I concluded that 35 ft. per coil would be sufficient to produce a serving temperature of 45 degrees or less depending on keg temperatures. To complete the look I borrowed a DIY tap design using magnets and removable metal fascias for ease of keg swapping. I also chose to include hinges and a latch for the door if only to allow one to not have to set down ones beverage whilst loading ice.

To complete the look I borrowed a DIY tap design using magnets and removable metal fascias for ease of keg swapping. I also chose to include hinges and a latch for the door if only to allow one to not have to set down ones beverage whilst loading ice.