Brewers Association

2015 Beer Style Guidelines

February 18, 2015

GERMAN ORIGIN ALE STYLES

German-Style

Kölsch

German-Style

Kölschs are straw to gold. Chill haze should be absent. Good, dense head

retention is desirable. Fruity-ester aroma should be minimally perceived, if at

all. Light pear-apple-Riesling wine-like fruitiness may be apparent, but is not

necessary for this style. Hop aroma is low and if evident should express noble

hop character. Malt character is a very low to low with soft sweetness. Caramel

character should not be evident. Hop flavor is low and if evident should

express noble hop character. Hop bitterness is medium. Fruity-ester flavors

should be minimally perceived, if at all. Light pear-apple-Riesling wine-like

fruitiness may be apparent, but is not necessary for this style. Diacetyl

should not be perceived. Wheat can be used in brewing this beer. Kölsch is

fermented at warmer temperatures compared to typical lager temperatures but at

lower temperatures than most English and Belgian ales, then aged at cold

temperatures (German ale or alt-style beer). Ale yeast is used for

fermentation, though lager yeast is sometimes used in the bottle or final cold

conditioning process. Body is light to medium-light; it is slightly dry on the

palate, yet crisp. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.042 -1.048 (10.5 -11.9) ●

Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.006 -1.010

(1.5 -2.6) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.80% -4.20% (4.80% -5.30%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 18 -28 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3 -6 (6 -12)

German-Style

Altbier

German-Style Altbiers are copper to dark brown ales,

originally from the Düsseldorf area. No chill haze should be perceived. A

variety of malts including wheat may be used to produce medium-low to medium

malt aroma. Fruity-ester aroma can be low. No diacetyl aroma should be

perceived. Hop aroma is low to medium. A variety of malts including wheat may

be used to produce medium-low to medium level malty flavor. Hop flavor is low

to medium. Hop bitterness is medium to very high (although the 25 to 35 IBU

range is more normal for the majority of Altbiers from Düsseldorf).

Fruity-ester flavors can be low. No diacetyl should be perceived. The overall

impression is clean, crisp, and flavorful often with a dry finish. Body is

medium. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.044 -1.052 (11 -12.9) ● Apparent

Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.014 (2.1 -3.6) ● Alcohol by

Weight (Volume) 3.60% -4.40% (4.60% -5.60%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 25

-52 ● Color SRM (EBC) 11 -19 (22 -38)

Kellerbier

or Zwickelbier Ale

Kellerbier

or Zwickelbier Ales are the color of the underlying German ale style.

Appearance may or may not be clear, so may appear slightly hazy to moderately cloudy.

Exhibiting a small amount of yeast haze is acceptable. These beers are

unfiltered, but may be naturally clear due to settling of yeast during aging.

Head retention may not be optimal. Kellerbier Ales are unfiltered German-style

Altbier and Kölsch. Aromas typical of the underlying beer style are present.

Fruity-ester levels should align with the filtered version, but may be

perceived at slightly higher or lower levels due to age and presence of yeast.

Yeast aroma is desirable, yet should be low to medium without overpowering the

balance and character of malt and hops. Low to moderately low levels of

yeast-generated sulfur-containing compounds should be apparent in aroma, and

low levels of acetaldehyde or other volatiles normally removed during fermentation

may or may not be apparent. Hop aroma is sometimes suppressed by the presence

of yeast, depending on style. Malt character will vary with style (see

individual style descriptions). Hop flavor is sometimes suppressed by the

presence of yeast, depending on style. Hop bitterness is sometimes suppressed

by the presence of yeast, depending on style. Yeast flavor is desirable, yet

should be low to medium without overpowering the balance and character of malt

and hops. Low to moderately low levels of yeast-generated sulfur containing

compounds should be apparent in flavor, and low levels of acetaldehyde or other

volatiles normally removed during fermentation may or may not be apparent. The

sulfur and acetaldehyde characters should contribute positively to the beer

drinking experience. These unfiltered German-style ales are packaged and/or

served intentionally with low to moderate amounts of yeast. Products may be

filtered and again dosed with yeast in the package, manifesting themselves as

bottle conditioned beers or unfiltered beer with yeast present. During

registration brewers may specify pouring instructions, choosing normal pouring,

quiet pouring or intentional rousing of yeast. Entries will be presented during

judging as specified by entering brewer. Body is variable with style. A

statement by the brewer explaining the underlying classic German ale style is

essential for accurate assessment in competitions.

Original Gravity (ºPlato) Varies with style (Varies with style) ● Apparent

Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) Varies with style (Varies with style) ● Alcohol

by Weight (Volume) Varies with style (Varies with style) ● Bitterness

(IBU) Varies with style ● Color SRM (EBC) Varies with style (Varies

with style)

Berliner-Style

Weisse

Berliner Weissbiers are straw to pale, the lightest of all the German

wheat beers. Appearance may be hazy or cloudy from yeast or chill haze.

Fruity-ester aroma will be evident at low to medium levels. No diacetyl should

be perceived. Hop aroma is not perceived. Malt sweetness is absent. Hop flavor

is not perceived. Hop bitterness is not existent to very low. The unique

combination of yeast and lactic acid bacteria fermentation yields a beer that

is acidic and highly attenuated. Fruity-ester flavors will be evident at low to

medium levels. No Brettanomyces character or diacetyl should be

perceived. Berliners are sometimes served with sweet fruit or herbal syrups.

Carbonation is high. Body is very low. At competition, subcategories for

unfruited and fruited or flavored versions of the style could be created. For

unfruited versions, brewer would indicate that no fruit or flavor has been

added. Fruited or flavored entries would be accompanied by a very brief

description of the fruit/flavor used by the brewer. Original Gravity

(ºPlato) 1.028 -1.032 (7.1 -8) ● Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato)

1.004 -1.006 (1 1.5) ● Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 2.20% -2.70%

(2.80% -3.40%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 3-6 ● Color SRM (EBC) 2 -4 (4

-8)

Leipzig-Style

Gose

Leipzig-Style Goses are straw to medium amber.

Appearance is cloudy/hazy with yeast character, may have evidence of continued

fermentation activity. Lemony or other citrus-like aromas are often present.

Some versions may have the spicy aroma character of added coriander at low to

medium levels. Horsey, leathery or earthy aromas contributed by Brettanomyces

yeasts may be evident but have a very low profile, as this beer is not

excessively aged. Hop aroma is not perceived. Malt sweetness is not perceived

to very low. They typically contain malted barley and unmalted wheat, with some

traditional varieties containing oats. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop

bitterness is not perceived. Lemony or other citrus-like flavors are often

present. Some versions may have the spicy flavor character of added coriander

on the palate at low to medium levels. Salt (table salt) character is also

traditional in low amounts. Horsey, leathery or earthy flavors contributed by Brettanomyces

yeasts may be evident but have a very low profile, as this beer is not

excessively aged. Traditional examples of Gose are spontaneously fermented,

similarly to Belgian-style Gueuze/Lambic beers, and should exhibit complexity

of acidic, flavor and aroma contributed by introduction of wild yeast and

bacteria into the fermentation. Low to medium lactic acid character is evident

in all examples as sharp, refreshing sourness. A primary difference between

Belgian Gueuze and German Gose is that Gose is served at a much younger age.

Gose is typically enjoyed fresh and carbonated. Overall complexity of flavors

and aromas sought while maintaining a balance between acidity, yeast-enhanced

spice and refreshment is ideal. Body is low to medium-low. At competitions,

brewers might provide supplemental information such as whether coriander, salt

and/or Brettanomyces is used and/or other information about the brewing

process. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.036 -1.056 (9 -13.8) ● Apparent

Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.012 (2.1 3.1) ● Alcohol by

Weight (Volume) 3.50% -4.30% (4.40% -5.40%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 10

-15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3 -9 (6 -18)

Contemporary

Gose

Contemporary

Goses are straw to medium amber, or, may take on the hue of added fruits or

other ingredients if present. Appearance is cloudy/hazy with yeast character, and

may have evidence of continued fermentation activity. A wide variety of herbal,

spice, floral or fruity aromas other than found in traditional Leipzig-Style

Gose are present, in harmony with other aromas. Horsey, leathery or earthy

aromas contributed by Brettanomyces yeasts may be evident but have a

very low profile, as this beer is not excessively aged. Hop aroma is not

perceived. Malt sweetness is not perceived to very low. They typically contain

malted barley and unmalted wheat, with some traditional varieties containing

oats. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop bitterness is not perceived. A wide

variety of herbal, spice, floral or fruity flavors other than found in

traditional Leipzig-Style Gose, are present in harmony with the overall flavor

profile. Salt (table salt) character is traditional in low amounts, but may

vary from absent to present in Contemporary Gose. Horsey, leathery or earthy

flavors contributed by Brettanomyces yeasts may be evident but have a

very low profile, as this beer is not excessively aged. Contemporary Gose may

be fermented with pure beer yeast strains, or with yeast mixed with bacteria.

Contemporary Gose may be spontaneously fermented, similarly to Belgian-style

gueuze/lambic beers, and should exhibit complexity of acidic, flavor and aroma

contributed by introduction of wild yeast and bacteria into the fermentation.

Low to medium lactic acid character is evident in all examples as sharp,

refreshing sourness. A primary difference between Belgian Gueuze and Gose is

that Gose is served at a much younger age. Gose is typically enjoyed fresh and

carbonated. Overall complexity of flavors and aromas sought while maintaining a

balance between acidity, yeast-enhanced spice and refreshment is ideal. Body is

low to medium-low. At competitions, brewers might provide supplemental

information which can include any herbs, spices, fruit or other added

ingredients, and/or information about the brewing process.

Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.036 -1.056 (9 -13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final

Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.012 (2.1 3.1) ● Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.50%

-4.30% (4.40% -5.40%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3

-9 (6 -18)

South

German-Style Hefeweizen

South

German-Style Hefeweizens are straw to amber. Because yeast is present appearance

may appropriately be very cloudy. The aroma of a German Hefeweizen is decidedly

fruity and phenolic. The phenolic characteristics are often described as

clove-like, nutmeg-like, mildly smoke-like or even vanilla-like. Banana-like

ester aroma should be present at low to medium-high levels. Hop aroma is not

perceived to very low. Malt sweetness is very low to medium-low. Hop flavor is

not perceived to very low. Hop bitterness is very low. These beers are made

with at least 50 percent malted wheat. No diacetyl should be perceived. The

flavor of a Weissbier with yeast is decidedly fruity and phenolic. The phenolic

characteristics are often described as clove-like, nutmeg-like, mildly

smoke-like or even vanilla-like. Banana-like ester flavor should be present at

low to medium-high levels. Hefeweizen is very highly carbonated. These beers

are typically roused during pouring and because yeast is present, the beer will

have yeast flavor and a characteristically fuller mouthfeel. Body is medium to

full. During competition, entries will be roused unless instructed otherwise

by the entering brewer. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.047 -1.056 (11.7

-13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.016

(2.1 -4.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.90% -4.40% (4.90% -5.60%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3 -9 (6 -18)

South

German-Style Kristal Weizen

South

German-Style Kristal Weizens are straw to amber. Appearance is clear with no

chill haze present. Because the beer has been filtered, yeast is not present.

The aroma is very similar to Hefeweizen; the phenolic characteristics are often

described as clove-like or nutmeg-like and can be smoky or even vanilla-like.

Banana-like ester aroma is often present. Hop aroma is not perceived to very

low. Malt sweetness is very low to medium-low. Hop flavor is not perceived to

very low. Hop bitterness is very low. These beers are made with at least 50

percent malted wheat. No diacetyl should be perceived. The flavor is very

similar to Hefeweizen with the caveat that fruity and phenolic characters are

not combined with the yeasty flavor and fuller-bodied mouthfeel of yeast. The

phenolic characteristics are often described as clove-like or nutmeg-like and

can be smoky or even vanilla-like. Banana-like ester flavor is often present.

Kristal Weizen is well attenuated and very highly carbonated. The beer will

have no flavor of yeast and a cleaner, drier mouthfeel than counterparts served

with yeast. Body is medium to full. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.047

-1.056 (11.7 -13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008

-1.016

(2.1 -4.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.90% -4.40% (4.90% -5.60%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3 -9 (6 -18)

German-Style

Leichtes Weizen

German-Style

Leichtes Weizens are straw to copper-amber. If served with yeast appearance may

appropriately be very cloudy. The phenolic and estery aromas typical of

Weissbiers are more subdued in Leichtes Weizen. No diacetyl aroma should be

perceived. Hop aroma is not perceived to very low. Malt sweetness is very low

to medium-low. Hop flavor is not perceived to very low. Hop bitterness is very

low. These beers are made with at least 50 percent wheat malt. The phenolic and

estery flavors typical of Weissbiers are more subdued in Leichtes Weizen. The

overall flavor profile is less complex than Hefeweizen due to decreased alcohol

content and there is less yeasty flavor present. No diacetyl should be

perceived. The German word leicht means light, and as such these beers are

light versions of Hefeweizen. These beers are often roused during pouring, and

when yeast is present the beer will have yeast flavor and a characteristically

fuller mouthfeel. Body is low with diminished mouth feel relative to

Hefeweizen. During competition, entries will be roused unless instructed

otherwise by the entering brewer.

Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.028 -1.044 (7.1 -11) ● Apparent Extract/Final

Gravity (ºPlato) 1.004 -1.008 (1 2.1) ● Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 2.00%

-2.80% (2.50% -3.50%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 3.5

-15 (7 -30)

South

German-Style Bernsteinfarbenes Weizen

South

German-Style Bernsteinfarbenes Weizens are amber to light brown; the German

word bernsteinfarben means amber colored. If served with yeast appearance may

appropriately be very cloudy. The phenolic and estery aromas typical of

Weissbiers are more subdued in Bernsteinfarbenes Weissbier. No diacetyl aroma

should be perceived. Hop aroma is not perceived. Distinct sweet maltiness and

caramel or bready character from the use of medium colored malts characterize

this beer style. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop bitterness is low. These

beers are made with at least 50 percent malted wheat. The phenolic and estery

flavors of this Weissbier should be evident but subdued. Bernsteinfarbenes

Weissbier should be well attenuated and very highly carbonated. No diacetyl

should be perceived. These beers are typically roused during pouring and

because yeast is present, the beer will have yeast flavor and a characteristically

fuller mouthfeel. Body is medium to full. During competition, entries will

be roused unless instructed otherwise by the entering brewer. Original

Gravity (ºPlato) 1.048 -1.056 (11.9 -13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final

Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.016

(2.1 -4.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.80% -4.30% (4.80% -5.40%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 9 -13 (18 -26)

South

German-Style Dunkel Weizen

South

German-Style Dunkel Weizens are copper-brown to very dark. If served with yeast

appearance may appropriately be very cloudy. The phenolic and estery aromas

typical of Weissbiers are more subdued in Dunkel Weissbier. No diacetyl aroma

should be perceived. Hop aroma is not perceived. Distinct sweet maltiness and a

chocolate-like character from roasted malt characterize this beer style.

Usually dark barley malts are used in conjunction with dark cara or color

malts. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop bitterness is low. These beers are made

with at least 50 percent malted wheat. The phenolic and estery flavors of

Dunkel Weissbier should be evident but subdued. Dunkel Weissbier should be well

attenuated and very highly carbonated. No diacetyl should be perceived. These beers

are typically roused during pouring and because yeast is present, the beer will

have yeast flavor and a characteristically fuller mouthfeel. Body is medium to

full. During competition, entries will be roused unless instructed otherwise

by the entering brewer. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.048 -1.056 (11.9

-13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.016

(2.1 -4.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.80% -4.30% (4.80% -5.40%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 10 -25 (20 -50)

South German-Style

Weizenbock

South

German-Style Weizenbocks are gold to very dark. If served with yeast appearance

may appropriately be very cloudy. Balanced clove-like phenolic and fruity-ester

banana elements produce a well-rounded aroma. If dark, a mild roast malt

character should emerge to a lesser degree in the aroma. No diacetyl aroma

should be perceived. Hop aroma is not perceived. Medium malty sweetness is

present. If dark, a mild roast malt flavor should emerge. Hop flavor is not

perceived. Hop bitterness is low. Balanced clove-like phenolic and fruity-ester

banana-like elements produce a well-rounded flavor. Carbonation is high. No

diacetyl should be perceived. These beers are typically roused during pouring

and because yeast is present, the beer will have yeast flavor and a

characteristically fuller mouthfeel. Body is medium to full. During

competition, entries will be roused unless instructed otherwise by the entering

brewer. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.066 -1.080 (16.1 -19.3) ● Apparent

Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.016 -1.028

(4.1 -7.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 5.50% -7.50% (7.00% -9.50%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 15 -35 ● Color SRM (EBC) 4.5 -30 (9 -60)

German-Style

Rye Ale

German-Style Rye Ales are pale to very dark, with

darker versions running dark amber to dark brown. Chill haze is acceptable in

versions packaged and served without yeast. In versions served with yeast,

appearance may range from hazy to very cloudy. Low to medium banana–like

fruity-ester aroma is typical; phenolic, clove-like aromas should also be

perceived. In darker versions malt aromas can optionally include low roasted

malt characters evident as cocoa/chocolate or caramel, and/or aromatic

toffee-like, caramel, or biscuit-like characters. Diacetyl aroma should not be

perceived. No yeast aroma should be evident in versions without yeast. Low to

medium yeast aroma should not overpower the balance and character of rye and

barley malt and hops in versions with yeast. Hop aroma is not perceived. Malt

sweetness will vary from low to medium. In darker versions malt flavor can

optionally include low roasted malt characters evident as cocoa/chocolate or

caramel, and/or aromatic toffee-like, caramel, or biscuit-like characters. Low

level roast malt astringency acceptable when balanced with low to medium level

malt sweetness. Versions packaged and served without yeast will not have yeast

flavor or fuller mouthfeel caused by yeast. Versions packaged and served with

yeast will have low to medium yeast flavor and a characteristically fuller mouthfeel,

which should not overpower the balance and character of rye and barley malt and

hops. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop bitterness is very low to low. Grist

should include at least 30 percent rye malt. Low banana-like fruity-ester

flavor is typical; phenolic, clove-like characteristics should also be

perceived. Diacetyl flavor should not be perceived. Body is low to medium. At

competition beers will be poured as instructed by entering brewer. During

registration brewer may specify pouring instructions, choosing normal pouring,

quiet pouring or intentional rousing of yeast. Original Gravity (ºPlato)

1.047 -1.056 (11.7 -13.8) ● Apparent Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008

1.016 (2.1 -4.1) ● Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.90%

-4.40% (4.90% -5.60%) ● Bitterness (IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 4

-25 (8 -50)

Bamberg-Style

Weiss Rauchbier

Bamberg-Style

Weiss Rauchbiers are a range of color from pale to chestnut brown. Because

yeast is present appearance may appropriately be very cloudy. Smoky malt

character ranging from low to high should be present in the aroma. The aroma of

a Weissbier with yeast is decidedly fruity and phenolic. The phenolic

characteristics are often described as clove-like, nutmeg-like, mildly

smoke-like or even vanilla-like. Banana-like ester aroma is often present at

low to medium-high levels. Hop aroma is not perceived. In darker versions a

detectable degree of roast malt may be present without being robust. Smoky malt

flavor ranging from low to high is present. Smoke character is not harshly

phenolic, but rather very smooth, almost rendering a perception of mild

sweetness. Hop flavor is not perceived. Hop bitterness is low. These beers are

made with at least 50 percent malted wheat. No diacetyl should be perceived.

The flavor of a Weissbier is decidedly fruity and phenolic. The phenolic

characteristics are often described as clove-like or nutmeg-like and can be

smoky or even vanilla-like. Banana-like esters are often present. Weissbier is

well attenuated and very highly carbonated. These beers are typically roused

during pouring and because yeast is present, the beer will have yeast flavor

and a characteristically fuller mouthfeel. Body is medium to full. During

competition, entries will be roused unless instructed otherwise by the entering

brewer. Original Gravity (ºPlato) 1.047 -1.056 (11.7 -13.8) ● Apparent

Extract/Final Gravity (ºPlato) 1.008 -1.016

(2.1 -4.1) ●

Alcohol by Weight (Volume) 3.90% -4.40% (4.90% -5.60%) ● Bitterness

(IBU) 10 -15 ● Color SRM (EBC) 4 -18 (8 -36)

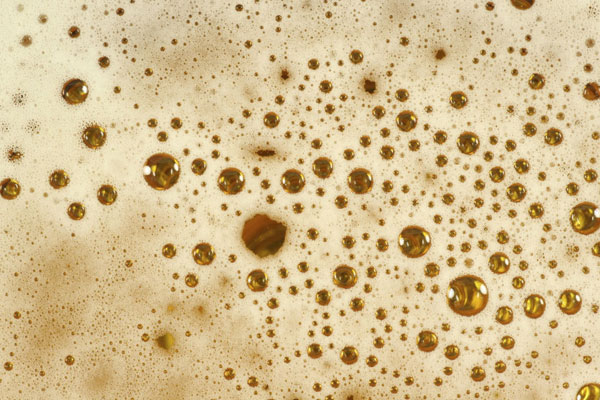

When people talk of nitro, it’s a reference to the type of gas used in the carbonation process. It means the difference between the creamier nitrogen beers (N2) and their lively, prickly CO2 counterparts. A typical nitrogenated beer contains about 70 percent nitrogen and 30 percent carbon dioxide.

When people talk of nitro, it’s a reference to the type of gas used in the carbonation process. It means the difference between the creamier nitrogen beers (N2) and their lively, prickly CO2 counterparts. A typical nitrogenated beer contains about 70 percent nitrogen and 30 percent carbon dioxide.

The brewery first released a bottled nitro version of Milk Stout to the public at the 2011 Great American Beer Festival. Sullivan and others pointed out that many breweries offer the same beer on both types of taps side by side. The difference between the two is vast, with the nitro beer taking on a creamy texture and more evenly distributed flavors while the CO2 beer is more aggressive on the tongue and aroma forward.

The brewery first released a bottled nitro version of Milk Stout to the public at the 2011 Great American Beer Festival. Sullivan and others pointed out that many breweries offer the same beer on both types of taps side by side. The difference between the two is vast, with the nitro beer taking on a creamy texture and more evenly distributed flavors while the CO2 beer is more aggressive on the tongue and aroma forward.

When people talk of nitro, it’s a reference to the type of gas used in the carbonation process. It means the difference between the creamier nitrogen beers (N2) and their lively, prickly CO2 counterparts. A typical nitrogenated beer contains about 70 percent nitrogen and 30 percent carbon dioxide.

When people talk of nitro, it’s a reference to the type of gas used in the carbonation process. It means the difference between the creamier nitrogen beers (N2) and their lively, prickly CO2 counterparts. A typical nitrogenated beer contains about 70 percent nitrogen and 30 percent carbon dioxide. The brewery first released a bottled nitro version of Milk Stout to the public at the 2011 Great American Beer Festival. Sullivan and others pointed out that many breweries offer the same beer on both types of taps side by side. The difference between the two is vast, with the nitro beer taking on a creamy texture and more evenly distributed flavors while the CO2 beer is more aggressive on the tongue and aroma forward.

The brewery first released a bottled nitro version of Milk Stout to the public at the 2011 Great American Beer Festival. Sullivan and others pointed out that many breweries offer the same beer on both types of taps side by side. The difference between the two is vast, with the nitro beer taking on a creamy texture and more evenly distributed flavors while the CO2 beer is more aggressive on the tongue and aroma forward.