Bad news: Starting tomorrow, you won’t be able to brew beer for about five months.

That’s the deflating message that 16th-century Germans subject to the BavarianBrauordnung (beer regulations) would have received. Fortunately, great innovations are borne of extreme limitations. From the Brauordnung sprung one of the world’s most hallowed warm-weather institutions: the beer garden.

The Brauordnung are often traced back to the year 1539, but Franz Hofer, who teaches German history at Cornell University and runs a beer blog, explained by email that the “decree limiting beer-brewing to the time between the feast of St. Michael [September 29] and that of St. George [April 23] wasn’t promulgated until 1553.” The decree came from Duke Albrecht V and applied only to Bavaria, the southeastern region that contains modern-day Munich.

There were two rationales behind this regulation. The first was that major fires were common throughout Europe at the time and Bavaria’s traditional wooden “fachwerk” architecture burned easily. Authorities feared that the coal fires used to heat breweries’ kettles might cause summer conflagrations.

The second reason, Hofer told me, was that Bavarians had discovered that fermenting lagers at cooler temperatures—between 39 and 55 degrees Fahrenheit—yielded a purer beer than ales brewed in warmer conditions. The Brauordnung, in fact, marked the point at which Germans started emphasizing lagers over ales.

The government orders also encouraged breweries to expand pre-existing beer cellars and build new ones next to their factories along the Isar River. These cellars, which were typically about 40 feet deep, were used to store beer brewed during the winter so that people would have something to drink between the dry months of May and September. Down in these cellars, beer barrels were covered in ice; to further ensure cool temperatures, breweries planted broad-leafed chestnut trees above the cellars for shade. Gradually, breweries began to scatter gravel and place tables underneath the trees. These areas, in turn, became popular drinking spots.

By the early 19th century, these watering holes had become so trendy that they were poaching patronage away from innkeepers and tavern owners. In response, innkeepers and tavern owners petitioned the authorities to revoke the breweries’ right to sell beer directly to the public. On January 4, 1812, Maximilian I, Bavaria’s first king, signed a compromise decree allowing brewers to continue selling beer but prohibited them from selling any food beyond bread. Thus was the biergarten, or beer garden, born.

Since Maximilian’s decree didn’t preclude Bavarians from bringing their own food to the breweries, the gardens became popular spaces to picnic. Bavarian beer gardens were permitted to sell food to their patrons again in 1897, but by then showing up with food from home had become a tradition. According to Hofer, the Bayerische Biergartenverordnung, a law passed in 1999 governing the sociocultural character of beer gardens, “Permits patrons to bring their own food into beer gardens, something that sets current Bavarian beer gardens apart from their counterparts in other German regions and Germanic countries.”

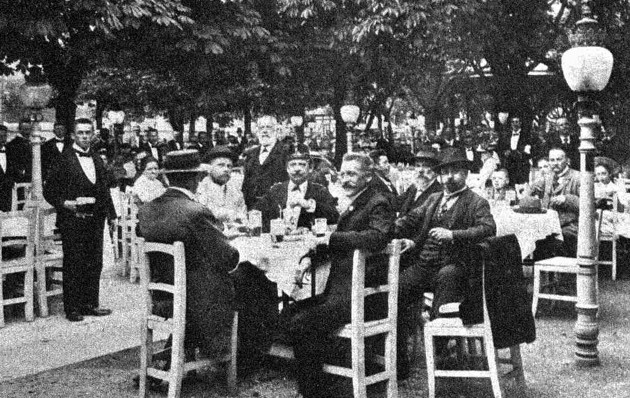

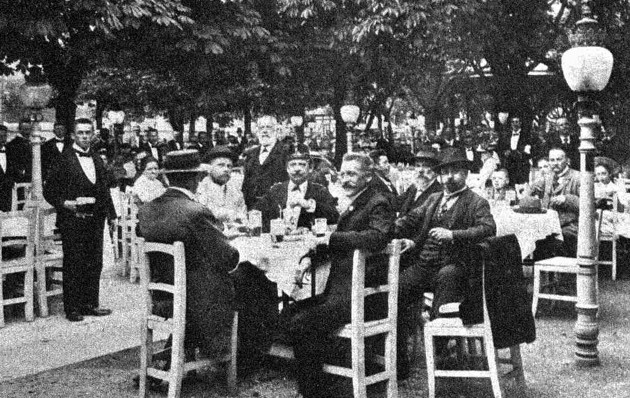

A beer garden in Vienna in 1902 (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, many of the most popular beer gardens in Munich date to the early 18th century. Perhaps the most famous, Augustiner-Keller, opened in 1807, even before the 1812 decree, according to spokesperson Christian Vogler. Some of the tables there have been passed down through generations of customers, as have the stories associated with them. Vogler told me the legendary tale of one table belonging to the German writer Sigi Sommer, who would fill a leftover pickle bucket with charcoal, light it on fire, and place it under the table so that he could keep warm while drinking in the garden during the winter. One day, he had drinks with a priest, Prälat Betzwieser, who had a wooden leg. A few beers in, they realized that Betzwieser’s leg had caught fire beneath the table. “When he left he could not walk straight,” Vogler recalled, “and you cannot blame the beer for it.”

It was a scene that Duke Albrecht V, in issuing some seemingly banal regulations back in the 16th century, probably never would have predicted.

The Brauordnung are often traced back to the year 1539, but Franz Hofer, who teaches German history at Cornell University and runs a beer blog, explained by email that the “decree limiting beer-brewing to the time between the feast of St. Michael [September 29] and that of St. George [April 23] wasn’t promulgated until 1553.” The decree came from Duke Albrecht V and applied only to Bavaria, the southeastern region that contains modern-day Munich.

There were two rationales behind this regulation. The first was that major fires were common throughout Europe at the time and Bavaria’s traditional wooden “fachwerk” architecture burned easily. Authorities feared that the coal fires used to heat breweries’ kettles might cause summer conflagrations.

The second reason, Hofer told me, was that Bavarians had discovered that fermenting lagers at cooler temperatures—between 39 and 55 degrees Fahrenheit—yielded a purer beer than ales brewed in warmer conditions. The Brauordnung, in fact, marked the point at which Germans started emphasizing lagers over ales.

The government orders also encouraged breweries to expand pre-existing beer cellars and build new ones next to their factories along the Isar River. These cellars, which were typically about 40 feet deep, were used to store beer brewed during the winter so that people would have something to drink between the dry months of May and September. Down in these cellars, beer barrels were covered in ice; to further ensure cool temperatures, breweries planted broad-leafed chestnut trees above the cellars for shade. Gradually, breweries began to scatter gravel and place tables underneath the trees. These areas, in turn, became popular drinking spots.

By the early 19th century, these watering holes had become so trendy that they were poaching patronage away from innkeepers and tavern owners. In response, innkeepers and tavern owners petitioned the authorities to revoke the breweries’ right to sell beer directly to the public. On January 4, 1812, Maximilian I, Bavaria’s first king, signed a compromise decree allowing brewers to continue selling beer but prohibited them from selling any food beyond bread. Thus was the biergarten, or beer garden, born.

Since Maximilian’s decree didn’t preclude Bavarians from bringing their own food to the breweries, the gardens became popular spaces to picnic. Bavarian beer gardens were permitted to sell food to their patrons again in 1897, but by then showing up with food from home had become a tradition. According to Hofer, the Bayerische Biergartenverordnung, a law passed in 1999 governing the sociocultural character of beer gardens, “Permits patrons to bring their own food into beer gardens, something that sets current Bavarian beer gardens apart from their counterparts in other German regions and Germanic countries.”

A beer garden in Vienna in 1902 (Wikimedia Commons)

Today, many of the most popular beer gardens in Munich date to the early 18th century. Perhaps the most famous, Augustiner-Keller, opened in 1807, even before the 1812 decree, according to spokesperson Christian Vogler. Some of the tables there have been passed down through generations of customers, as have the stories associated with them. Vogler told me the legendary tale of one table belonging to the German writer Sigi Sommer, who would fill a leftover pickle bucket with charcoal, light it on fire, and place it under the table so that he could keep warm while drinking in the garden during the winter. One day, he had drinks with a priest, Prälat Betzwieser, who had a wooden leg. A few beers in, they realized that Betzwieser’s leg had caught fire beneath the table. “When he left he could not walk straight,” Vogler recalled, “and you cannot blame the beer for it.”

It was a scene that Duke Albrecht V, in issuing some seemingly banal regulations back in the 16th century, probably never would have predicted.

No comments:

Post a Comment