Notes

| Water Profile: Ca 135 | Mg 1 | Na 10 | SO4 71 | Cl 186 |

In keeping with popular approaches to brewing this style, I chose to use a yeast strain that many have come to identify as quintessential, Wyeast 1318 London Ale III, and built a single large starter using 2 packs the morning prior to brewing.

Later that day, after the sun had set, my assistant accompanied me to the garage to help prepare for the following morning’s brew day, starting with measuring out and milling the slightly different amounts of Maris Otter.

I then weighed out the flaked oats and tossed them on top of the milled grain.

Left: Oats. Right: NOats

Since these would both be 5 gallon batches, I opted to use the

no sparge method and collected the full volume of brewing liquor for each into separate kettles. The chemistry of the water used to make “proper” examples of NEIPA is often said to be far richer in chloride than sulfate, and so using Bru’n Water, I adjusted each batch to a sulfate to chloride ratio of about 0.38 (71:186). Around noon the next day, I began

heating the strike water for the oats batch first then, 20 minutes later, doing the same for the batch with no oats, lamely referred to as “NOats” henceforth.

When the temperature of the water was slightly higher than suggested, it was transferred to a mash tun and allowed to preheat for a few minutes before I incorporated the grains, both batches ultimately settling at my target mash temperature.

Both batches were mashed for 60 minutes and stirred briefly every 20 minutes throughout. I took the time to measure out hop additions as the mashes rested.

Once the mashes were complete, I performed a vorlauf then began collecting the sweet wort, noticing what seemed to be a subtle and unsurprising difference in color.

Left: Oats | Right: NOats

Hops were added at the listed times during separate 60 minute boils.

Replacing hop stands with later kettle kettle additions meant the wort was chilled immediately at flameout, quickly dropping to about 72°F/22°C.

A hydrometer measurement at this point revealed a slight difference in OG, with the Oats wort clocking in a little lower than the NOats wort.

Left: Oats 1.056 OG | Right: NOats 1.058 OG

Separate 6 gallon PET carboys were filled with equal amounts of wort from either batch then placed in a temperature regulated chamber to finish chilling. While waiting, I

stole some yeast from the starter to reserve for future use then split the rest evenly between two smaller flasks in preparation to be pitched. It took about 4 hours for the carboys of wort to stabilize at my target fermentation temperature of 67°F/19°C, at which point the yeast was pitched. Both beers had developed healthy kräusens and were bubbling like mad 18 hours later.

18 hours post-pitch

Yet another unique aspect of brewing NEIPA is adding dry hop additions during active fermentation, a step purported by some to be the cause of the so-called “juicy” hop character due to a process referred to as

biotransformation. Because of this, I added the dry hop charges 2 days after pitching yeast, when it seemed the kräusen had peaked, about 4 days sooner than I would have for a West Coast IPA.

Dry hop additions added 2 days post-pitch

As fermentation finished up over the following few days, I was met with a glorious aroma every time I opened the chamber, which while nice, left me wondering if any would remain in the finished beer. Activity was all but absent a week post-pitch so I took an initial hydrometer measurement that I compared to a second measurement 3 days later, the lack of change confirming fermentation was indeed complete.

Left: Oats 1.010 FG | Right: NOats 1.010 FG

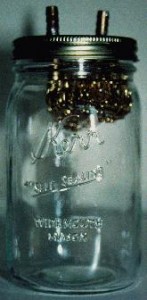

I dropped the temperature on the chamber to 32°F/0°C and let the beers cold crash overnight, forgoing my standard

gelatin fining in order to

preserve whatever it is some fear is lost by fining. I returned the following evening to keg the cold beers.

While I’d originally planned to add a charge hops in the keg as well and actually did suspend them in the kegged beer, I quickly learned the fishing line I used disallowed the o-ring on the keg to seal when pressure was applied. Dammit! After removing and tossing over 8 oz/227 g of sopping Galaxy, Citra, and Centennial, I burst carbonated the beers by applying 45 psi of CO2 to each keg. After 18 hours, I reduced the gas to 14 psi where it remained for 3 days until I began serving it to participants. Perfectly carbonated, nice white head with fantastic retention, and hazy as hell. Whatever I did right felt so wrong.

Left: Pats | Right: NOats

Results

A total of 19 people of

varying levels of experience participated in this xBmt. Each participant was served 1 sample of the Oats IPA and 2 samples of the NOats IPA then asked to identify the sample that was unique. Given the sample size, 11 tasters (p<0.05) would have had to correctly identify the Oats beer as being different in order to reach statistical significance. A total of 6 tasters (p=0.65) accurately identified the unique sample, indicating participants in this xBmt were unable to reliably distinguish a NE-style IPA made with 18% flaked oats in the grist from one made without any flaked oats but an otherwise similar recipe.

This xBmt was discussed live on The Brewing Network’s 11/21/2016 episode of The Session. Adding the data of the 4 blind co-hosts who evaluated the beers, only 1 of which correctly identified the Oats sample as being unique, brings the total number of participants to 23 with 12 (p<0.05) expected correct responses in order to reach statistical significance and 7 (p=0.69) actual correct responses. Ultimately, the performance of this set of participants roughly approximates the larger dataset’s inability to reliably distinguish between the Oats and NOats beers.

My Impressions: Despite all the sh*t I’ve talked on hazy IPA over the last few years, I was pretty excited to brew one for myself and especially curious about the impact of flaked oats. As far as my ability to distinguish between these beers goes, I could reliably tell them apart based on appearance alone, as the Oats batch had a lighter color that, to me, made it look more juice-like and less murky than the NOats beer. Other than that, I couldn’t do it. I didn’t necessarily expect them to taste and smell different, which they didn’t, but what really got me is how remarkably similar they were in terms of mouthfeel, both possessing what I could see being described as soft or even creamy with a luscious body that I always presumed came from flaked oats.

I feel I owe it to my hazy IPA loving friends to share that this was probably the best IPA I’ve ever made. Yeah, I know, it almost hurts to say it. I enjoyed it so much that I started drinking pints before data collection and worried I might not have enough if I didn’t practice some moderation. Citrus and tropical fruit stole the show with whispers of earthy dankness I believe came from the Galaxy. So, so good. At least for the first 10 days after kegging. At the time of writing this, the beers had been on tap for exactly 4 weeks and were certainly showing their age, though not to the point of being undrinkable.

Discussion

Hazy New England/Northeastern IPA has permeated the craft beer world and, ugly as it may be to some, is almost certainly here to stay. In addition to its unconventional appearance, NEIPA is lauded for its soft mouthfeel and creamy texture, which many believe to be a function of the high percentage of flaked oats in the grist. However, participants’ inability to reliably distinguish a version of NEIPA made with 18% flaked oats from one made without flaked oats sort of throws a wrench in this theory. I’ve used varying amounts of flaked oats numerous times in the past in styles ranging from American Amber to Imperial Stout and I’ve never had an issue with clarity. Since both beers in this xBmt were similarly hazy and neither dropped clearer than the other over time, I’m beginning to question whether flaked oats really does contribute to haze as much as I’ve been led to believe.

So, what is the cause of haze in NEIPA? And what about the creamy, “juicy” character so quintessential to this style? While yeast in suspension is certainly a possibility, I’m doubtful because, for one, I’ve tasted yeasty beers many times and don’t enjoy them, plus I’ve yet to have gastrointestinal issues after drinking multiple pints of my xBmt beers. Since all we’re left with is speculation at this point, I find myself leaning toward a couple other explanations. Water chemistry being as imporant as it is, it seems pretty obvious the proportionately high chloride levels used to produce NEIPA is responsible for some of the uniqueness, though it

may not be a main cause of haze. What I’m most interested in exploring further, a topic that has received little focus up until recently, is the impact of biotransformation that occurs from the interaction of yeast with hops added during active fermentation.

One thing I’m convinced of is that flaked oats and perhaps other similar grains do have an impact on the appearance of the finished beer, just not necessarily the haziness. To me, the NOats IPA’s darker color gave it a murky appearance reminiscent of dirty dish water, while the version made with oats had more of an orange hue that I found much more appealing. It’s because of this that I will continue to use flaked oats in future batches of NEIPA.

As is often the case, these results have left me with more questions than answers, a good thing for the curious like me. In addition to its impact on NEIPA, I can’t help but wonder what effect flaked oats actually has on styles where it more traditionally makes up a portion of the grist. Could it be that our perception of Oatmeal Stout as possessing a silky mouthfeel and creamy texture is driven more by expectation than reality? I don’t know, but I look forward to trying to figure it out!